Counterfeit goods flood Bangladesh; is BSTI asleep?

Consumers across Bangladesh have been facing a growing risk due to substandard and counterfeit products in markets, raising questions whether BSTI and other regulatory bodies are working effectively to safeguard the public against low-quality and harmful products.

Everyday items from edible oils and spices to bottled water and cosmetics -- often fail to meet required standards.

Jamshed Mia, a resident of Mirpur, recounted buying branded soybean oil that smelled and felt unusual once opened at home. “You can’t check the quality in the shop. Only at home do you realise its poor quality,” he said.

When he returned to the retailer, his complaint was refused.

Visiting New Market, Karwanbazar, Chankharpul and major supermarket chains, the UNB correspondent found shelves stocked with low-quality, expired, or counterfeit goods including rice, lentils, spices, cooking oil and bakery items.

Despite occasional mobile court drives, long-term monitoring and consistent enforcement remain weak.

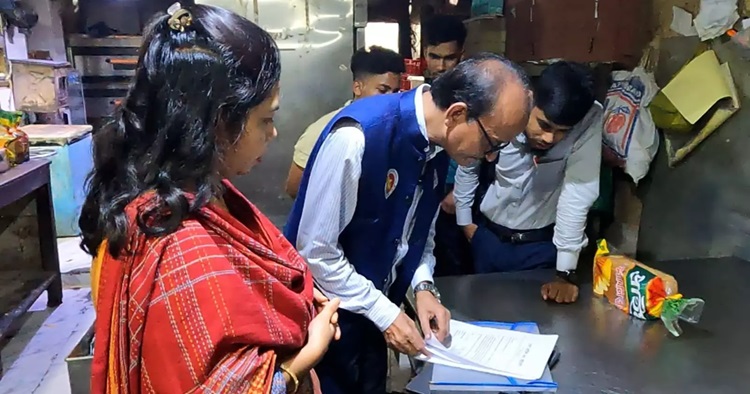

The Directorate of National Consumer Rights Protection and the Bangladesh Standards and Testing Institution (BSTI) occasionally conduct mobile court drives.

While media coverage of such raids is widespread their impact rarely lasts.

On September 17, a BSTI-led operation in Moghbazar fined Rowza Shop Tk 15,000 for selling mustard oil, honey, turmeric powder, chili powder and ghee without proper certification or packaging. The shop was also instructed to obtain the required license immediately.

“If the drive is taken seriously, sellers dare not display the products. But the situation highlights poor surveillance in the market,” said Hasim Mollah, a private sector employee.

A shop owner, speaking anonymously, said, “Whenever raids are conducted, traders stay cautious for a few days. After that, they continue business as usual with fake or low-quality goods.”

Recent BSTI actions include shutting down a company producing bottled water in unhygienic conditions without proper testing.

Officials said the plan failed to maintain health and safety protocols and lacked basic laboratory testing and certification.

Medical specialists and consumer rights activists have also raised concerns over cosmetics, particularly skin-whitening creams.

Many of these products contain mercury, steroids, and other harmful chemicals, causing permanent skin damage, kidney problems and hormonal imbalances.

Traders and importers said BSTI primarily tests products during licensing or upon complaints, leaving street-level vendors and small factories largely unmonitored.

Hasuar Ali, a trader of Karwan Bazar said, “Thousands of companies operate without BSTI licenses and their products reach rural shops. Many people consume these items which can seriously harm their health. Authorities must be more vigilant to prevent illegal operations.”

It is also alleged that selective enforcement, bribes and political or business influence often shield large companies.

Monirul Islam of Atlas Cosmetic Limited said, “Raids rarely target big companies. Officials often ignore them because they are influenced by money or politics.”

Talking to UNB some consumers said the existing penalties for food adulteration, fake certification, or substandard goods are too low to deter big offenders as most operations and labs are Dhaka-based.

Regional presence is too weak to cover nationwide supply chains, they said.

Bangladesh has thousands of brands but only a handful of laboratories and inspectors.

One inspector may cover multiple districts, making regular checks impossible.Some consumer rights activists said BSTI inspections focus mainly on branded products in urban supermarkets and the result is widespread circulation of substandard or counterfeit goods.

Weak Mandatory Certification

BSTI’s oversight of products requiring mandatory certification remains alarmingly weak, exposing consumers to substandard and even counterfeit goods.

Although about 315 items fall under compulsory BSTI approval, sustained market surveillance is rare. Surprise checks are infrequent, while many small factories and importers openly use fake BSTI logos with little risk of penalty.

The agency has only a handful of labs and inspectors as often one officer covers several districts, making routine monitoring impossible.

Even when violations are detected, fines are so small that businesses often find it cheaper to ignore standards. Enforcement disproportionately targets small traders, while politically connected groups and substandard imports frequently escape scrutiny.

Unsafe bottled water, edible oils, cement, baby food and electrical goods regularly reach consumers without valid certification. Rural markets are virtually unmonitored, and customs controls on imported electronics, cosmetics, and processed foods remain lax.

Experts blame limited laboratory capacity, weak enforcement and poor coordination among regulators for the persistent gaps, warning that the lack of accountability puts public safety at risk.

Contacted, Md Saiful Islam, Director (CM) of BSTI, told UNB that the BSTI is understaffed and 1,600 more employees will be recruited and 41 new district offices will soon open. “We are always active in controlling and eliminating counterfeit products. But most culprits flee when they detect our presence,” he said.

Meanwhile, the government has introduced stronger legal measures reforming the Copyright Act 2023, the Trademarks Act 2009 and the Customs Act 2022 for tackling intellectual property violations.

Official said the National Board of Revenue’s (NBR) Customs Wing has been working closely with international partners, including the World Customs Organization and neighbouring countries, to curb the entry of counterfeit goods into Bangladesh.